Nonverbal until age four, Dr. Stephen Shore was diagnosed with “atypical development” and “strong autistic tendencies.” Labeled “too sick” for outpatient treatment, Dr. Shore was recommended for institutionalization. With support from his parents, teachers, wife, and others, Stephen is now a professor at Adelphi University where his research focuses on matching best practices to the needs of people with autism.

In addition to working with children and talking about life on the autism spectrum, Dr. Shore is internationally renowned for presentations, consultations and writings on lifespan issues pertinent to education, relationships, employment, advocacy, and disclosure. His most recent book, College for Students with Disabilities (purchase here), combines personal stories and research for promoting success in higher education. In the following interview, we asked Dr. Shore about the important components of self-advocacy and how organizations and businesses can work to build more opportunities for autistic adults.

MHAF: What do you think professionals in the community can do to create a trusting relationship with a client on the autism spectrum?

Stephen Shore: It starts with the “3 A’s of Autism”.

The first “A” is Awareness of what autism is. From the level of the individual to companies, organizations, communities, and even entire countries, there has been great effort made by [several organizations] in increasing general awareness of what autism is. This step is critical as a pathway to the next step: Acceptance.

The second “A”, or Acceptance, involves understanding that autism is something to work with rather than doing something to and connecting with the individual where they are at. If that means sitting on the floor and flapping with them to open a connection, that’s where you start. That’s how my parents connected with me. That said, while my parents accepted me for who I was, they knew a lot of hard work was needed in order for me to lead a fulfilling and productive life.

The third “A”, or Appreciation, is when the person with autism is valued for who they are. Examples of achieving this third stage include companies such as Microsoft and SAP that actively seek individuals on the autism spectrum having highly developed skills in information technology. That said, it’s important to realize that people with autism often have skills in other areas that need to be considered for employment as well.

MHAF: What advice can you give to parents of adults with autism in regards to focusing on their abilities rather than their disabilities, and supporting them during the transition process?

SS: Asking the question “what can the person with autism do?” rather than focusing on only the “can nots.” Certain autism brings significant challenges. If that were otherwise, we wouldn’t be here trying to figure it all out. That said, we must remain cognizant and provide support for the challenges. However, at the same time we must keep in mind how to successfully engage the strengths of people on the autism spectrum.

MHAF: How can society as a whole move from a deficit model to an abilities-based model?

SS: This is a great question recognizing we need to transition from thinking of autism in terms of disorder, deficit, and disability to a model of ability. No one makes a career out of doing things they are not good at, so neither should individuals with autism. Given that people with autism tend towards a widely varying skill set with extreme challenges coupled with significant strengths, it is especially important to ask “what can the individual do?”

MHAF: How can teachers transform their curriculum into a model that is designed to accommodate every student and fits the needs of autistic individuals?

SS: In two words: universal design. By keeping in mind and accounting for all learning styles in the development of curriculum and delivery, education reaches a wider diversity of students. In general, what is good for students with autism – be it providing different ways of receiving information, processing, and demonstrating mastery of subject material – tends to be good for everyone else. For example, common accommodations such as an advanced organizer, a copy of the teacher’s notes, or a timeline for completing a multipart project can be helpful to all students.

MHAF: How can parents and professionals who work with adults on the spectrum provide for them the tools needed for self-advocacy?

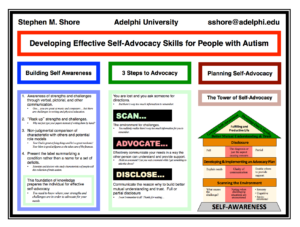

SS: Successful self-advocacy requires a firm foundation of the individual with autism understanding what it means to them to be on the autism spectrum. As described in the poster below, this building of self-awareness enables the person to 1) scan the environment to recognize when challenging situations occur; 2) develop an advocacy plan to effectively communicate needs for accommodation or greater understanding in a way the other person can provide support; and 3) disclose the reason why this greater mutual understanding or modification is needed. Often I am asked when it is appropriate to advocate. If the effect of having autism significantly impacts a situation and there is a need for a better mutual understanding, then it’s important to develop an advocacy plan.

MHAF: How can we, as a society, take action to ensure inclusion in the workplace?

SS: Similarly to including individuals with autism in education, combined with focusing on what the person with autism can contribute to the workplace, will be most productive for engaging those with autism in the workplace. Research suggests that the most highly weighted variable for career success is how well that individual gets along with others, which requires a high emotional quotient (EQ). This directly translates to what is often the biggest challenge for people on the autism spectrum in finding and keeping a job – facility with a workplace social interaction piece, or soft skills. In view of this challenge, Robert Naseef and I have developed a 40-hour training program, entitled “Softskills for Employment,” to enable individuals with autism to successfully enter the information technology field and stay there. This program was successful in on-boarding about two dozen young adults with autism to the software giant SAP.

Again, it must be emphasized that not all people with autism are “IT geeks” and that we need to make sure that those individuals with other skill sets achieve success in finding and maintaining employment.

AUTHOR

AUTHOR “Emily’s” Lesson from the Heart

“Emily’s” Lesson from the Heart